Note: This is an excerpt from the new book User Experience Design: A Practical Playbook to Fuel Business Growth, available now.

It’s not just electric motors that set Tesla apart as a car company. The relative newcomer successfully combined deliberate and thorough experience design efforts with disruptive technologies to gain a significant advantage over competitors. Despite the price premium on many models, the demand for Tesla’s cars is so high that the company can’t keep up with production—as of August 2021, there was a 4–6 week wait for the Performance Model 3 and a 5–6 week wait for the Performance Model X. But the sought-after cars are part of a much bigger experience that begins the moment the prospective owner starts considering the vehicles.

99% of automotive shoppers begin their purchase journey expecting to be frustrated.

A Better Buying Experience

If ever an experience warranted a redesign, it would be buying a car. In the traditional scenario, tense, drawn-out negotiations with salespeople working on commission and against quotas leave consumers cold. A study by DrivingSales found that 99% of automotive shoppers begin their purchase journey expecting to be frustrated. It’s an experience fraught with distrust: Half of consumers reported they will walk if the dealer requires a test drive before giving a price and 43% will bolt if they’re required to give personal information upfront. By contrast, the same study reported that 56% of shoppers would buy more cars if the process was easier, and auto sales could rise about 25% if the experience was better.

Tesla differentiates itself by alleviating the many pain points in car shopping. First, they sell directly to customers, rather than licensing products through independent dealerships. This gives them control over their customer-facing ecosystem—how they present their vehicles and how their employees express information about the company and their products.

When the customer is ready to purchase, they use an in-store digital design center, during which pricing is non-negotiable (read; non angst). A car can also be purchased remotely on Tesla’s website, making the same customizations in a process that feels similar to buying a laptop online. Tesla has a delivery team responsible for guiding the customer through payment, document signing, and delivery. When the car is ready, the customer signs all the documents online and can pick it up at a dealership or if they choose have it delivered to a convenient location.

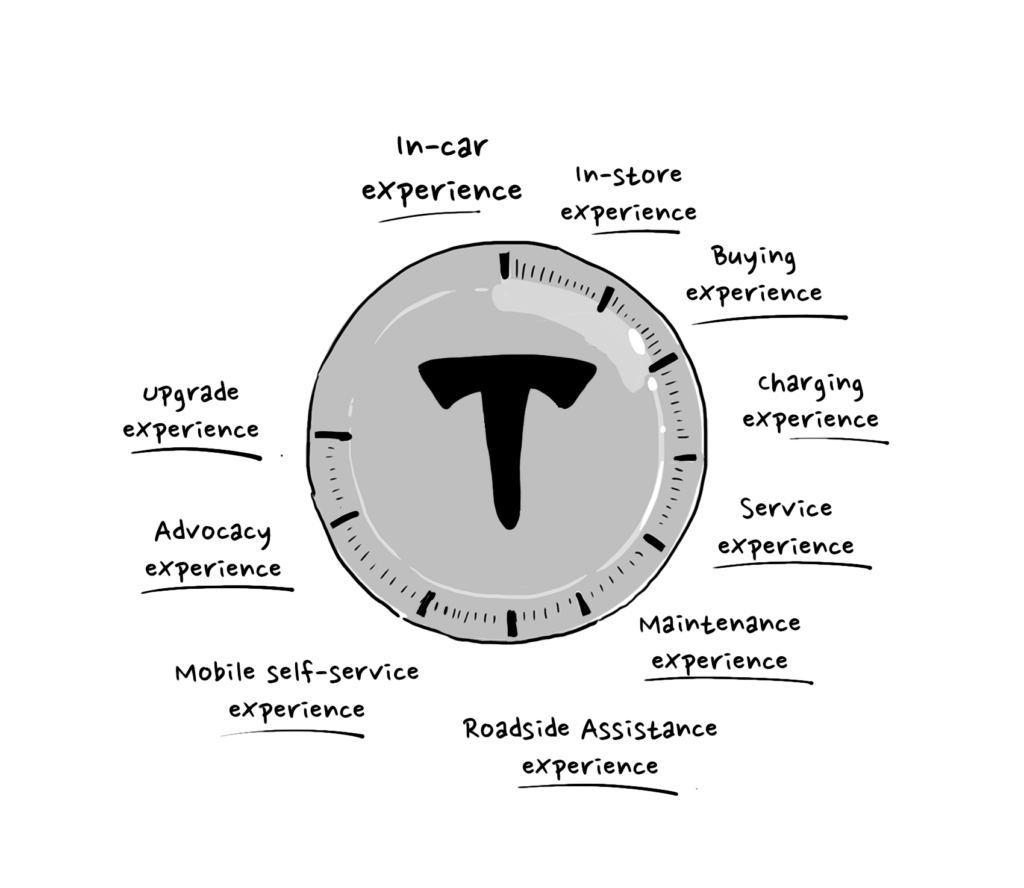

This revitalized car-buying experience shows a deep understanding of several of the plays described in this Playbook—in particular, the User Empathy Play (Chapter 14: User Empathy Play) and Experience Ecosystem Play (Chapter 18: Experience Ecosystem Play), which allows organizations to build an intimate and binding understanding of their customers. That accrued empathy allows brand leaders to map a customer’s optimal experience and design each touchpoint along the way. Tesla excels at fine-tuning each step, starting from the moment a prospect looks into buying a car and continuing through their experience as an owner.

Experience That Lasts A Lifetime

The Tesla experience doesn’t end once the customer gets their new car. Rather, this is when the experience can really begin to take flight and delight. Leveraging technology to create better customer experiences enables Tesla to offer innovations like at-home wireless software updates that other companies aren’t even remotely equipped to match. Plus, approximately 80% of repairs can be completed remotely, free of charge—a huge incentive for anyone who hates spending time and money at the auto repair shop. When service center repairs are necessary, they’re generally completed four times faster than at a conventional repair shop (as the same amount of care is spent in designing the experience for the dealership employees. Of course, technology alone didn’t create these exemplary experiences—great experiences don’t just happen, they are deliberately designed.

This deliberate design shows up immediately in the physical design elements of the cars. With the Model 3, the minimalism serves as both a reflection of the company’s design aesthetic as well as a testament to Tesla’s philosophy that cars shouldn’t be complicated. Once inside, a large touchscreen replaces the conventional cluster of control knobs and buttons. (The only familiar button inside the vehicle is the control to activate hazard lights above the windshield.)

The more subtle elements of design show up in the experience of driving the car. There are a whole host of Easter egg features in the operating system that continue to delight customers. Take Chill Mode, for instance, which provides a smoother ramp- up to speed designed to help drivers avoid unintentionally exceeding the speed limit. There are also settings that allow parents to monitor the speed and location of teen drivers. And while the touchscreen has many available shortcuts to make it easier to access certain controls, the temperature, music, and navigation can also be voice-activated. Because so much of the car is controlled by the operating system (OS), the driving experience improves with each update. This iterative approach was seeded early on. When Tesla released the Model S in 2012, they sold 100,000 units to early adopters, allowing them to gain deep and detailed insights from a contained cohort of drivers as they continued to iterate the innovative design of the car.

“We obviously cannot compete with the big car companies in size,” CEO Elon Musk has said of Tesla, “so we must do so with intelligence and agility.” That agility is reflected in the corporate culture he’s created, which dictates that: “Anyone at Tesla can and should email or talk to anyone else according to what they think is the fastest way to solve a problem for the benefit of the whole company. Moreover, you should consider yourself obligated to do so until the right thing happens.”

This is indicative of the kind of organizational design thinking that has put the company in position to act on a broader innovation strategy that will allow consumers around the world to gather, manage, and store their own electrical sources (something that’s already underway with Tesla’s home solar panels and batteries). This kind of thinking can be put into practice using the Design Problems and Opportunities (Chapter 34: Design Problems and Opportunities Play) , which helps identify the right problem to solve and then find a solution that benefits the organization and its customers. By eliminating outdated business hierarchies and focusing on solving problems both internally and for customers, Tesla has a distinct edge.

Good Design is Good Business

Despite inconsistent profitability, quality problems in its luxury cars, and a slow production schedule, Tesla has quickly become the world’s most valuable automaker. Their success has spurred competition in the electric vehicle space, but no other automakers have been able to compete (they have built an economic moat through engineering and experience design). Audi, Jaguar, and Porsche recently added new electric models, and there are more budget-friendly options like the Chevy Bolt and Nissan Leaf, but combined they’ve barely made a dent in a U.S. market dominated by Tesla.

According to Car and Driver, “Tesla’s Apple-like ‘one-stop experience’ proved a huge plus for owners. Its ability to manage all aspects of EV purchase and ownership—sales, financing, service, fast charging, and route planning that incorporates fast charging—were cited by an overwhelming 91% of owners as a reason to buy another Tesla.

This “Apple-like” user experience is the kind of technology ecosystem that traditional automakers will find extremely difficult to replicate. The fact that Tesla’s entire business model is built around using technology to design great ownership and driving experiences gives them a tremendous advantage over traditional automakers headed into the EV market. They also maintain a big leg up on like-minded newcomers, Rivian and Polestar, whose head of U.S. operations, Gregor Hembrough, recently conceded to The New York Times, “Right now, there’s only one party in town”.